Flexible Labor, Rigid Capital

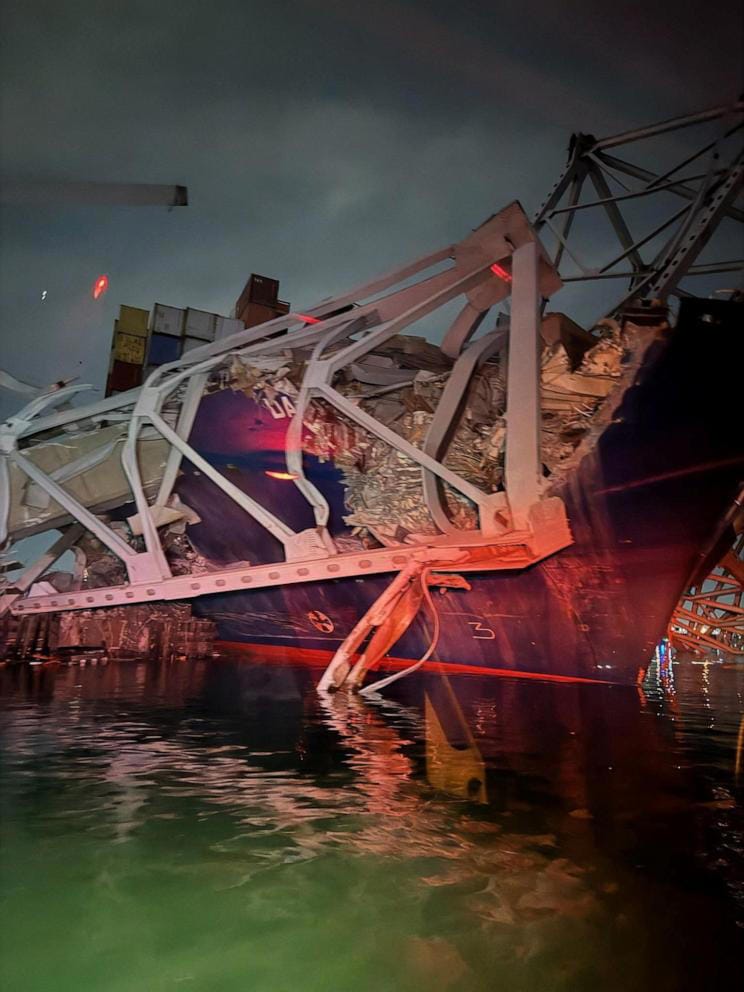

At around 1:45 AM this morning, March 26th, a container ship, the Dali, flagged out of Singapore, was leaving the port of Baltimore when it briefly lost power and control. That brief loss of power - in the video of the incident it appears to occur for only a few seconds - led the ship to crash into one of the support pillars of the Francis Scott Key bridge, which spanned the Patapsco river, and which collapsed entirely within seconds. The state and city claim there are still seven people unaccounted for, and I hope that that estimate is correct, or even high, although I'm not optimistic.

It is a small mercy that this accident occurred in the middle of the night rather than during rush hour. News continues to develop, and, as ever, I'm just a girl with an internet connection. I'm going to stick to broader claims and arguments, and I hope that it is clear that this is meant to help me (and therefore, anyone who reads this) make sense of the world in which we're living, and the horror and fury I feel waking up to this situation.

While the immediate concern is for the safety of the people on the bridge, the results of this disaster will be far reaching. It will be incredibly difficult, expensive and likely slow to clear the wreckage from the area - and for the duration of the project, the port will be closed.

The Port of Baltimore is, by tonnage, the fifth busiest port on the Eastern Seaboard. It handled about 265,000 containers in 2023, about 1/3 as many as the port in Norfolk and about 12% of what is handled annually in the massive New York/Newark complex.

It is likely that this amount can be picked up by other ports, although the global shipping system is already facing severe disruption from the Houthi attacks in the Red Sea, drought-lowered water levels in the Panama Canal, and continued insecurity in the Black Sea thanks to the war on Ukraine. Container ships were already backed up across the Eastern Seaboard by January. Shipping companies have been facing significant rerouting over the last few years, increasing the cost of shipping in terms of fuel spent, cargo spoilage, and war risk/conflict insurance and security.

These cost increases are then experienced as inflation in the cost of commodities and goods. In the case of fuel, which overwhelmingly goes through the Red Sea, this can have a spiraling inflationary effect as transporting the fuel gets more expensive, which increases the cost of the fuel, which then again increases the cost of shipping the next batch of said fuel, etc.* This also increases emissions as ships travel both further and faster to make up for differences.

But for the city of Baltimore, there is no simple rerouting and replacing the economic activity represented by the port. A mechanical failure in a single ship, lasting for a few moments, can not only kill a huge number of people in a single horrifying moment, but can lead to cascading local and global economic consequences. And while the city has claimed otherwise, a diesel smell pervasive across the bay was reported and the possibility of an ecological disaster is also clearly present.

More immediate ironies abound. A ship called the Dali sitting stuck in a river with steel beams draped across it like, say, melted clocks. And, as Gary Alexander wrote on Blusky, there is "something darkly poetic about infrastructure, named after the guy who wrote the national anthem, getting taken out by something losing control of its rightward turn".

While it would come as no surprise to discover that the disaster of the Dali reflects a failure of safety regulations - akin to the failures we've witnessed in railway freight, Boeing, and other transportation and infrastructure disasters - and it is possible the crew could've done something different that would have averted the disaster (and the way automation and price cutting has lead to extremely limited crew counts on these vessels may also have contributed to any crew error), I think it is worth underlining that the crash was first and foremost a mechanical failure, the power on the ship went out.

Thus, a brief mechanical failure in a single ship can lead to consequences that reverberate across the global economy. This eventuality was more comically underlined in March 2021, when the container ship the Ever Given got stuck in the Suez Canal. And perhaps more interesting to people interested in the revolutionary potential of infrastructure disruption, the Houthi attacks on the Red Sea have dropped shipping through the Suez by over 60%, and lead to drastic and dramatic transformation of global shipping patterns which, according to historian and shipping expert Sal Mercogliano, is potentially the largest disruption of shipping since the world wars.

The just-in-time supply-chain economy, in which elaborate global information and logistical structures allow companies to respond in real time to shifts in market availability and demand, is often described with terms like "flexibility". This is most infamously practiced in the fast fashion industry, in which companies can track exactly how certain styles are selling live in all of their stores around the globe, and adjust how much of each garment, style, size or design they are making so rapidly that within a few weeks slight shifts in consumer preferences are reflected in store inventories.

A particular sundress sells out in Southern California, store managers across the region request resupplies, a research analyst in Bangalore recognizes the blip, who informs a marketing team in New York that sends orders to production management in Hong Kong, who mobilize four different contractors in Bangladesh, who order more of the particular cloth pattern; the factory that makes that pattern hires fifteen temp workers to meet this sudden demand, which they then ship to the sweatshops where the design is sown, the sweatshops crank out a quadruple order of the popular sundress, which a Cambodian truck driver takes overland to Shanghai, where it will take flex space in a pre-booked shipment (organized by a Vietnamese subcontractor) and move across the Pacific in a container ship built in South Korea owned by a Swedish company and registered in Panama, crewed by an Indonesian captain with a Filipino crew using navigation software designed in Norway. All of it happening within a few weeks.

But this kind of "just-in-time" production and information forward economy is also reflected in "surge pricing", "print-on-demand" technologies, drop-shipping Amazon storefronts, and any other variety of borderline scammy business models that allow companies and retailers to scale particular pieces of their operations up and down at incredible speeds.

As we have seen from the Houthis, from Supply Chain Inflation, and will likely now see from the Baltimore Port disaster, this "flexibility" is built on a severely rigid set of conditions. Logistical outcomes must go smoothly. When the system is working well, sellers have a level of flexibility in inventory management, price setting and demand response that retailers thirty years ago could only dream of. But one small disruption - a single ship having a mechanical failure, a single political actor attacking a particular choke point - can have untold cascading effects, effects that require massive geopolitical and economic efforts to adjust for.

In classic capitalist ideological fashion, rather than supple, flexible and strong, the system is in fact incredibly rigid and brittle, amplifying small problems into massive disasters. What is actually made flexible is the work force--who can be easily hired and fired to meet demand, who can be "offshored" or avoided entirely if they protest, unionize, or otherwise see wage increases. Precarity, surplus population status and an explosion of slums, scams and grey markets are the results.

This massive system offloads the insecurity and costs of this constantly changing "flexible" arrangement onto the workers, who pay through their bodies, their wages, their lives a cost that used to be held by the capitalist firms as "risk". This risk took the form of inventory and warehousing, sales competition and the basic vagaries of fads and fashions when it came to consumer demand, and more structural fluctuations when it came to basic commodities.

But this mass downward redistribution of risk and flexibility has also put tremendous strain on "nature" itself, through the acceleration of emissions and waste produced by this mode of production. Workers and the ecology of our planet have paid for the construction of this system. But the physical world and the social world have real limits to what they will take.

Container ships are HUGE, and so even a very small error in their navigation or functioning can doom any bridge or other piece of infrastructure they might crash into. Capitalism has built a global system of extreme inertial forces featuring narrow chokepoints that have massive cascading effects, and its own logic forces it to continually cut back on the forms of protection - regulation, prepared and trained staff, physical maintenance - that might shield itself from some of these consequences.

The Houthis have demonstrated one such form of this infrastructural vulnerability. So, tragically, has the Dali. As ecological and social crises compound, more and more of these chokepoints will become obvious and visible. The question of liberation or fascism may hinge on whether we can force those chokepoints closed ourselves, or whether the state will be empowered to manage the fall-out.

UPDATE: 3/26 4:45PM EST. It turns out the missing (and presumed dead) are 6 migrant shift-workers who were repairing potholes on the surface of the roadway. According to another worker from the contractor company, Brawner Builders, they hail from El Salvador, Mexico and Guatemala. Thus the systemic global redistribution of precarity, death and disaster was already in full force the moment the Dali struck the bridge.

*I am convinced by the "Supply Chain Theory of Inflation" - which was originally put forward by anarchist journal Strange Matters - that sees inflation being driven not by money supply like we learn in high school history (and which national banks attempt to manage with interest rates), nor by the recently popular and populist "greedflation" theory, which argues that corporations are price-gouging because they can get away with it, but by spiraling price rises caused by supply chain disruption. While greedflation likely exists and has small effects on consumer pricing, it cannot explain economy wide inflation – particularly in commodity, parts and wholesale prices. The supply chain theory, meanwhile, successfully explains why inflation spiked again in February--which is about the amount of time it would take for the Houthi rerouting driven to effect the global supply chain.