Image Without Metaphor

Dune Part Two and the Return of Socialist Realism

We are living through an era of thudding cultural literalism. In our narrative products (movies, TV and to a lesser but noticeable extent, novels) that has meant that instead of story we get plot, premise and lore, dialogue is replaced by exposition, emotion evoked only by music cue and cliche. The characters are structural objects of the plot, pure reflections of their social and narrative positioning, stripped of messy contradiction or conflictual desires. Whenever an artist even introduces any kind of metaphor they make sure to explain it tidily and neatly by the end, like a kid elbowing you in the ribs going "did you get it did you get it?", meaning the best we can hope for is parable or fable.

Though this trend was already visible in the 2010s--particularly in the lore heavy franchise cinema of superheros, star wars, and dinosaur parks--the aesthetics remained fast and furious. An undeniable kinetic energy, combined with a reflexive meta-irony ("well, that just happened") hardly meant these films would be interesting or good, but it left room for cinematic pleasures outside of the constraints of the film's worlds: you could enjoy them as a movie, as entertainment, they were popcorn fodder that didn't demand you inhabit them entirely, although doing so was the best way to overlook their faults.

And they were counterposed with an incredibly rich period of genre production (particularly in the work of Jordan Peele and so-called "elevated horror"), that was full of deeply evocative, metaphorical and overwhelming confusion and feeling, and was, importantly, incredibly popular. There was an undeniably "mass" audience for both. But as elevated horror became a sellable and apeable style, we were treated to increasingly literal and on-the-nose stories. (I promise a full essay about this is coming soon, lol).

The truly huge films of the last two or three years have had even less space for self-reflection or individual analysis. There seems to be an allergy to ambiguity, a desire for orderly storytelling and image making that leaves little to the imagination or debate. What better symbol for this plasticine anti-intellectualism than a "feminist" reimagining of Barbie, which was, as people caught up in the hype cycle didn't want to admit to themselves, the launch event for Mattel's new Adventure Theme Park in Arizona and the Mattel Cinematic Universe, which will bring us Lena Dunham's Polly Pocket movie and Daniel Kaluya's Barney the Dinosaur later this year.

This literalism is also present in "higher" art: 2023's Palme D'or and Oscar winning Anatomy of a Fall (a movie I really did like!) is an uncomfortably direct process film, depicting every step of a death and murder trial in painstaking and frank detail. Stylistically it is marked by long, still shots of people talking. There is no montage, the camera barely moves, which works to produce a claustrophobic atmosphere that reflects the violent claustrophobia of the family, state and justice system.

But beyond such observation of its aesthetic effectiveness, there is little to say about the film, little to analyze. The film shows you and tells you what it is. In Justine Triet's hands this is quite the experience, as we get great and subtle performances from the actors and a few deeply resonant and painful moments (though I much prefer the manic intensity of her previous film, Sibyl). But in the hands of Hollywood directors this tendency is a deadening bore.

It is quite appropriate at the same moment that Denis Villeneuve's visually arresting but utterly inert Dune Part Two was becoming the first bonafide box-office hit of 2024, Christopher Nolan was winning the Oscars for best-director and best film.

Nolan is truly the patron saint of this kind of plot-and-premise only literalist filmmaking. Elsewhere, writing about the way the NFT grift operated, I described what I called the Christopher-Nolan effect. (sorry for self-quoting but I dont feel like trying to rephrase this. blogs!)

If you explain an incredibly simple premise — like, for example, “a guy forgets everything every five minutes” or “you can go inside people’s dreams and make false memories” — over and over in increasingly abstruse ways, the person it’s being explained to will eventually tell themselves, “I just don’t get it.” This effect is only strengthened the more people there are agreeing that the matter at hand is “cool,” “interesting,” or “complicated” — a process of mass, self-inflicted intellectual gaslighting.

This kind of audience-condescending premise-forward literalism is not just in the narrative and scripting, it's in the acting. The actors of Dune 2 almost all speak in that tedious whisper-growl that stands in for profundity, a vocal-style also popularized by Nolan, in Christian Bale's portrayal of the caped crusader in 2005's Batman Begins. I believe that if a movie features a bunch of good actors and all the performances are flat and dull, as is the case in Dune Part Two, where even Florence Pugh, Lea Seydoux and Josh Brolin lack all charisma, it is ultimately a reflection on the director (and the script), not the actors.

For example, Javier Bardem plays a tribal/military leader and religious zealot of the Fremen, Stilgar. The Fremen are a nomadic people living in the desert wastelands of Arakkis, a planet colonized by the aristocratic empire the protagonist Paul Atreides (Timothee Chalamet) comes from. The planet is the source of Spice, which is the fuel that makes interstellar transport possible, but the imperial control of it is violent and ecologically devastating. In case the middle east/oil comparison wasn't clear, however, the faith of the Fremen is pretty straightforwardly space-Islam.

Stilgar believes in a prophecy that a messiah, the Mahdi, is coming to save the Fremen from the imperium. In this prophecy, that messiah comes from outside of the planet--Paul Atreides is that messiah (yes, it's giving Lawrence of Arabia). Javier Bardem, an incredibly talented actor, spends the entire movie pointing to something Paul has just done and saying "See! This is proof he's the Mahdi!" Once or twice this is comical. But by the film's climax it's so tedious that, when Paul demonstrates his power to a war council of the Fremen leadership and the camera cuts to Bardem yelling "The Mahdi!" someone behind me in the audience said loudly to their friends "this is so stupid."

A thing that Dune, Barbie and their ilk has over 2010s blockbuster franchise cinema, however, was how often the latter was visually ugly. Sleek high-tech and militaristic production design, CGI used to create "realistic" looking aliens and alien planets that achieved said "realism" via flat grey, purple and olive tones (particularly in the MCU), everything either drenched in gloom or over-exposed with washed out flourescent brightness. The deep saturated colors and inventive camera tricks of the A24/prestige horror style offered a visual relief to these ugly 200 million dollar CGI spectacles.

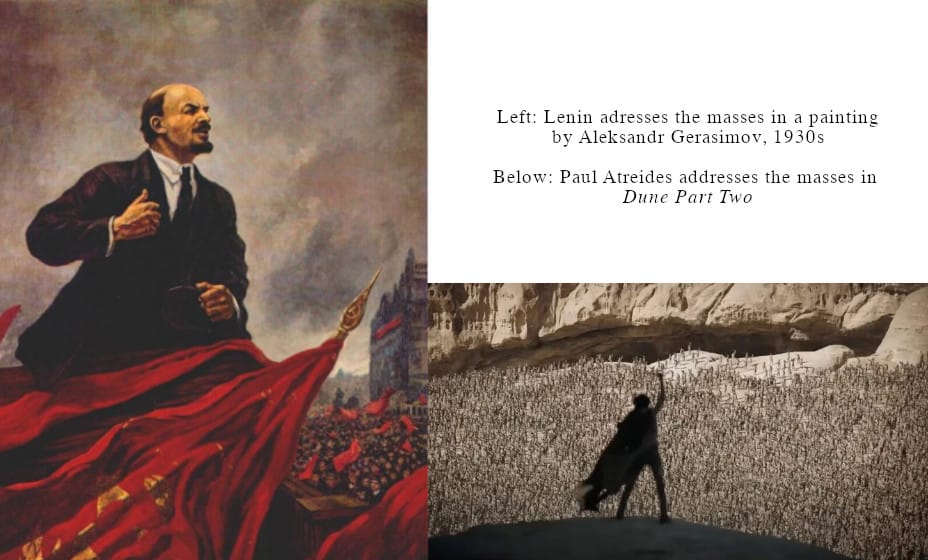

The blockbuster film of the last few years has achieved a synthesis of these two trends: color-rich saturated imagery, hammer on the head straightforward storytelling. I think that the actual visual pleasure offered by these new films is such a breath of fresh air that they disarm people's critical faculties (See also: Everything Everywhere All At Once, The Banshees of Inishiren, Saltburn). What has emerged reminds me most of the USSR's most maligned aesthetic legacy, socialist realism.

Dune Part Two looks good, but the images are incredibly static, people are reduced to flat images, with the exceptions of the sudden outbreaks of violent action, which are themselves short lived and poorly staged. We get loads of long shots showing people framed by huge amounts of space, and all the spaces are empty of other human beings. There is almost no montage. Characters stand alone in a frame, often at the center of a more or less symmetrical image, evoking the fussy-fascist aesthetics of Wes Anderson. We see epic throne rooms and massive desert vistas, but the only things visible are the characters and the landscape: narrative information. It is stripped down, but it is not minimalist. The production design and color are rich, and, in the case of Dune, often really cool. But they convey nothing beyond "wow, cool world building" and "look at this protagonist/antagonist, influencing and going against huge forces"

There is perhaps no better example of this than the moment of boldest aesthetic gesture in Dune Part Two. When we visit the home base of the evil Harkonnen, the Nazi-proximate fascist villains, the whole film goes to black and white. This is an effective aesthetic critique of the current fascist movement, whose de-saturated militarism is best captured in the black and white Blue Lives Matter flag, as demonstrated in this brilliant comic essay by Nate Powell.

The scene stands out because it actually tries to convey information metaphorically, but it undercuts even this unsubtle and blatant communication by the fact that the sequence is introducing a new antagonist who we haven't seen before, and so its black-and-white also conveys narratively that this is the "origin story" of sorts of the character. (And in case the aesthetics don't convince us, we watch Harkonnen leaders killing their underlings over and over and over and over again, which is the cheapest most annoying shortcut to "this is a bad guy" in modern cinema and which is so repetitive in Dune Part Two it approaches parody)

Every moment in the film is used to either move plot forward or explain the world's lore, visually or verbally. Almost every single line of dialogue in this film is exposition. For the first twenty minutes or so, I was patient, thinking "ok, this is a sequel, they're reintroducing the world but eventually the movie will start." But no, even the very final lines of the film are just an explanation of what's happening. It's so incredibly clunky and on the nose that I couldn't believe more people weren't talking about it. That's when the socialist realism comparison clicked for me.

To see why, we need to take a brief detour to art history and revolutionary Russia! (The Vicky ACAB promise, lol). Although the social revolution initiated in February 1917 had been strangled in its crib by the Bolshevik counterrevolution by 1921 (at the latest), there had still been a massive unleashing of cultural and social energies that were embodied in the art of the period and reverberated well into the twenties.

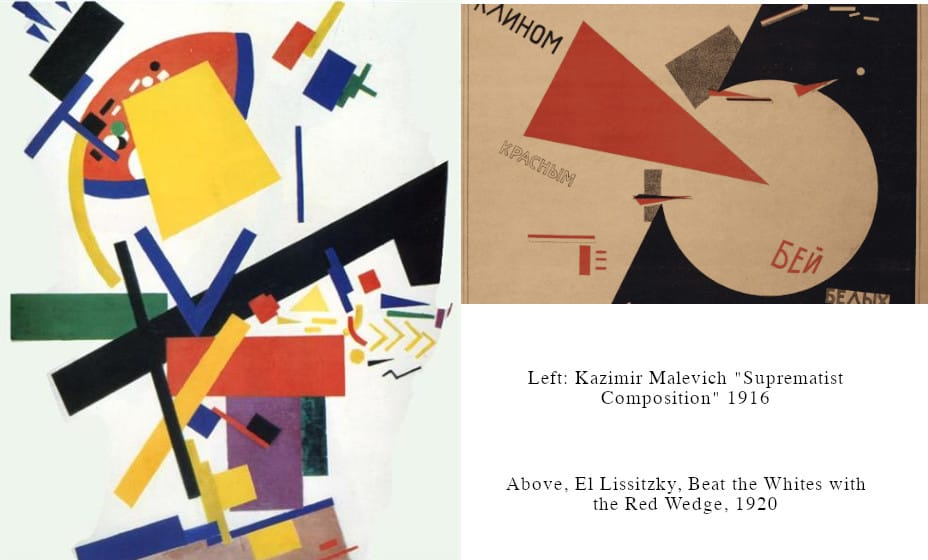

This was the period where every European art movement had a named ism and a manifesto or three. Two avant-garde visual art movements, Suprematism (which emerges slightly before 1917) and Constructivism, which themselves are influnced by an anti-colonial nationalist art movement called Russian Primitivism, became dominant styles within the USSR. While Suprematism is associated most strongly with the oil paintings of Kazimir Malevich, Constructivism is immortalized less in oil paintings then in the beautiful poster-art that adorned soviet cities and towns across the period.

Both movements featured bold colors and abstract geometric designs. Although artists moved back and forth between the two styles, and they were often associated in the press and the public mind, they differentiated themselves strongly from one another theoretically: supermatism was based in an art-for-arts-sake purely symbolic register, while constructivism was meant to express the political and materialists stakes of the moment (it frequently featured slogans and text in its compositions). In this way, the distinction between the two is quite similar to the dichotomous cinema theories of Kino-Eye (as put forward by Dziga Vertov) and Kino-Fist (Sergei Eisenstein), but finishing this thought would require well and truly heading down a rabbit hole.

Anyway, at the same time that these styles were duking it out in journals and galleries, an art style known as social realism, whose most famous proponent today is probably Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, was also ascendant in the USSR. This style favored direct address, simple representational images of people and events, and was meant to hold and embed a simple political and propagandistic message for the people (the word "propaganda" did not have a distinctly negative connotation in the period).

This form of direct, "meet the people where they're at" literalism was the preferred style of the Stalinist bureacuracy. As the Bolshevik state took greater and greater political and economic hold of the country, it also began to exhibit stronger and stronger control over cultural and artistic expression. Though across much of the West social realism was fading by the early 30s, the USSR made it the official policy of the state that all art--visual, narrative, poetic and dramatic--must be in the style of Socialist Realism. The bureaucracy enforced this through murder, political purges, secret policing, and all its other favored tactics.

Why do I detour into all this history? Well, I think it may have some explanatory power for this moment of intense aesthetic literality we're living through. What the Stalinist state was attempting to do was to reign in creative and subversive energies that had been unleashed by the revolution. Socialist Realism was a style that maintained a kind of vulgar political communication and appearance of radicalism while removing any of those pesky, confusing, arousing and otherwise thought-provoking tendencies of the abstract and avant-garde movements. I believe the current trend toward literalism is a similar ideological attempt to stifle unruly energies, desires and dreams.

I would be remiss to pretend there is just one simple explanation for the current trend, which I think is built on the back of many different tendencies. Major studio video game story-telling standards and IP/franchise cinema both contribute greatly to the kind of lore-focused psychologically-disinterested narrative style. The fascist destabilization of meaning, combined with the collapse and polarization of journalism and magazines, as well as AI's weakening of other forms of public information and data, may lead to a craving for clarity and simplicity. The click-driven discourse machine, which features video "explainers" for endings and emotional beats in every movie and tv show, no matter how obvious and clear, certainly adds to the Christopher Nolan effect. And the reduction of anti-racist and feminist struggles into "representation" has also created a tendency for people to describe the presence of women or people of color as progressive in and of itself, and has led to a defensive reflex in artists to try to outflank critique by wearing their politics on their sleeve.

But I think there is something even more epochal going on: culture is reacting to a fundamental break in the timeline. Three events in the US-the COVID pandemic, the George Floyd Rebellion, and the January 6th coup attempt, fundamentally transformed our society and unleashed tremendous energy and anxiety. Everything is confusing and out of control, and during lockdowns, revolutionary upheaval, pandemic layoffs and fascist transformations we culturally reconsidered what our future might look like, what the world might have to be. It forced a deep introspection, a rethinking and reshaping of society and our daily lives.

The literal deterministic storytelling of Dune or Barbie or Oppenheimer attempts to put the cat back in the bag, to soothe the audience by seemingly bold aesthetic vision while actually telling quite dull and lifeless stories that ask little of the imagination. Don't worry, we'll explain everything to you, no need to think, no need to imagine.

You can see how effective this is in way people talk about Dune Part Two. Because in 2024, I don't find it hard to believe that people are incredibly excited by the vision of an anti-colonial guerilla movement driven by Islamic faith defeating a massive and technologically dominant empire. But, outside a few Arab voices, shockingly few people are connecting the appeal of Dune at this moment to the desire for Palestinian liberation. This is because while they may yearn for it deep inside, ideologically it is almost impossible for even the most conscientous ally in the imperial core to truly allow themselves to name and imagine Palestinians defeating Israel militarily and winning. Slave resistance and decolonial victory is, as Zubayr Alikhan wrote, literally unthinkable in the imperial mind.

I do find it hard to believe that more people in 2024 aren't outraged that Dune Part Two literally features a talking embryo, an embryo that we constantly see shots of. The embryo is being carried by Paul's mother, Jessica, and the two of them constantly refer to "her" (the fetus) and her desires and thoughts. But lest we get confused, and think that perhaps Jessica's discussion of the fetus and its desires is a way of evoking and establishing power and authority for herself, in one of the shots of the embryo we see it "open its eyes"--that's right, a few month old embryo has fully developed human eyes, eyelids, etc--letting us know that in fact not only is this clump of cells alive, conscious, it is psychic, wise, forward seeing. This is anti-abortion propaganda of the nastiest kind.

In other words, despite all the attempts of the literalists, the movies still contain resonances and ideas beyond their control. The pleasure (or, in the case of ideological production, danger) of creating culture is that it maintains meaning well outside and beyond the intentions of the artist, writer or producer. But I do think the current trend of literalism is of a piece with a liberal deadening of the moment, an attempt to deradicalize and defang society, social critique, and the population, through an anti-intellectualism that dresses itself up in elaborate aesthetic gestures and epic fantastical narratives.

Do not abandon the messy, conflictual and difficult space of desire, poetry and metaphor. The clarity on offer is the clarity of a one-way mirror in a police interrogation room. What you are being given to see is what you already know, while out of sight power makes eye contact you cannot join, watches your gaze, observes your reactions, and plans its next move.